For those of you looking for the sequel to this blog it is at: Mosley's in Kenya

Paul and Rebecca Mosley in Ethiopia

Friday, August 30, 2024

Thursday, August 22, 2024

Postlude: The Realization of a Long Deferred Hope

|

| Bereket arriving at Dulles |

The week proved to be momentous in a number of ways that are worth recording here.

Rebecca, David, and I returned from our home leave on August 5th, this time to Kenya. It was a start to our new life and we arrived in the late evening. Rebecca will recount the events of our first week in Nairobi, but I knew that I had one more trip to Ethiopia planned the following week to finish several tasks that had not been concluded prior to our departure in June. This included canceling my work and residence permits (a requirement by the govt. to keep our organization in good standing). I also needed to sign a few official documents over to the new Ethiopia Rep., bring some new computers and supplies from the US, and pick up the cat and bring it back!

|

| Sisay at desk with former Reps in photo. |

One task that was added during our time in the US was a plan to accompany Bereket, our dear friend who actually got his US visa for attendance in College in the US (EMU). He went for the visa interview 2 days after we left. We did not have much hope despite momentous efforts to maximize his chances on the second attempt. And they did bear fruit. I received a Whatsapp at 2am saying he had been accepted!

(Aside: I relived the horrific moment 12 months before when I dropped him at the embassy and waited outside. After a year of applications for college, TOEFLs, SATs, getting IDs and a passport, only to be rejected days before his departure is almost too traumatic to relive. The drive back to our compound... The details are recounted here A Hope Deferred ). I since found out that the acceptance rate for F-1 visas for admitted students from Ethiopia is about 15% on the first try and less on the second. This was a miracle!)

|

| Bereket's family |

In addition to all of this, I planned to also move our last 6 50lb suitcases and the cat to Kenya on my flight out. That along with Bereket out of the country was sufficient for a fair amount of anxiety about departing at the end of the week.

I flew out last Sunday evening. The trip from Nairobi to Addis is very short, less than 2 hours. I arrived and was met my Wondwesen, our Logistics Officer. I was really happy he wanted to pick me up as it made the trip back that much easier. I was fairly well loaded with stuff for Ethiopia that I intended to leave there.

It was late when I arrived. When I arrived in the compound I was greeted profusely by Fikre one of our guards and even more so by Bella and Friday our dogs. Sisay and his family were already asleep as it was late, and I did not want to disturb them. The plan was for me to stay in the guest container. It was a nice bookend to my first arrival during the handover from Bruce and Rose. I spent 2 weeks there before eventually moving into the house. It is not uncomfortable and Friday (the dog) and Charly (the cat) were happy to join me on the bed the first night. (although they were not very keen on sharing between each other.)The next morning I joined Sisay and his wife Tazita for breakfast in the house. It was pretty much exactly how we left it except that they had bought some new living room furniture (This was a year overdue!) They seemed to be very comfortable and I was happy they had settled into it so well. Yeshi the cook arrived a bit later as well as the MCC staff. It was good to greet everyone, and I had a fair amount of work to do in the office in the morning.

The first order of business though was to go with Wonde to the Labor office and begin the process of cancelling the work permit. They claim to have a very streamlined process, that is supposed to be entirely online, but it does not work. Predictably we spent about 8 hours there on Monday and did not complete-- being asked for things that were not listed as required on the website. Wonde went back on Tuesday and finished the job and honestly, I don't think any expatriate has succeeded in canceling their work permit in less than 24 hours as we did. This is thanks to Wonde nurturing connections in all of these offices. (Still, I was glad that as an Ethiopian, Sisay would not need to go through any of this process!)After canceling a work permit, the next step in the process is to cancel my residence permit and obtain an exit visa so I can leave the country legally. One might think that once the work permit was cancelled this process would be fairly automatic, but it is not. In fact, the immigration office has been making this process very difficult for expats, and it can take over a week even when the request is accepted. You can pay a high fee for an expedited process though, which is what I intended to do.

.jpg) |

| Wonde and I have coffee after failing at immigration |

Checkmate. They had actually created an impossible situation for me. I had to leave Saturday. I could not get an exit visa for a month. My only option was to leave again with my residence permit (it had not been canceled since my application was not approved). But since I am not coming back, Wonde will have to clear this permit in my absence next month. This will cost MCC Ethiopia a hefty fine. And if he does not do so and I ever return to Ethiopia I am likely to be arrested. It was very distressing to realize that I would have to leave in these circumstances, but I had no choice.

Having failed completely at immigration had the minimum value of allowing me to use the rest of the week to do many of the other tasks at hand. And there were many. One thing I needed to do with Sisay was to go to some meetings with partners for final handover discussions. This became extremely important the currency had devalued 100% in the past 2 weeks. This completely annulled the Grant Agreements we had with several partners that had grants based on the previous birr value to the USD. We had productive meetings with Food for the Hungry and Action Against Hunger about their project grants. The floating birr means that MCCE can have a USD account in country. This has never been possible in Ethiopia and has huge implications for the program grant distributions and MOUs going forward.

I admit, I am sighing some relief that this particular issue is not my problem. Kenya has enough challenges that I will need to deal with. The Ethiopia program has even more. I am really thinking that God's hand was in the timing of our departure to have an Ethiopian Country Director at this time. I think Sisay is particularly well qualified for the challenges that are coming up in Ethiopia.

Among the other tasks on my checklist was a dinner with Bereket to describe in detail what it is like to walk into an airport, go through security, check-in, immigration, and get on a plane. He has never done any of those. While I was planning to be in the airport with him, there was no guarantee we could be together long. I let him know there were bathrooms on a plane, the food was free, there were movies to watch, and turbulence was not dangerous. I am guessing those last few days before departure were completely surreal for him.I also had a chance to go over to his house. His dad Muluneh, is one of our house security guards and has been with MCC for about 20 years. He and his wife Yelfign graciously invited me and Sisay over with Bereket to their house. We had a nice Ethiopian meal and talked about ways they could communicate with Bereket. They cannot speak or read English but Bereket left them a smartphone with Whatsapp so they can at least call, and receive photographs. We talked a long time about Bereket leaving. His parents truthfully, are thrilled he can have this opportunity, and thanked MCC for the help we all gave in making this opportunity possible.

I made a number of contacts with our vet, and a vet. service in Kenya to be sure Charly had all the correct documentation to travel. This was a point of great stress as I feared the cat's documentation might prevent me from getting on the plane on Saturday morning. I was assured all was in order and I was to bring her to the ticket window and she would go in cargo. I had to trust this was true.

On the second to last day I became very anxious about imagining traveling with 6 large suitcases. a backpack, carry-on suitcase and a cat. I did not think it was possible. On an impulse I drove to the enormous Ethiopian Cargo hangars and asked if I could ship 4 suitcases airfreight. When I pulled up in my car to one of about 30 truck bays and wandered in, with no help from my logistics officer, I think they thought I was insane. So a kind clearing agent directed me through a process that went to half a dozen different offices and people in different places, over about 3 hours. But at no point was I prevented from accomplishing the task. I could not believe it. I succeeded in getting my 4 bags into airfreight all by myself!! It was the opposite of the immigration experience.That gave me peace of mind, knowing that I would only have 2 suitcases to manage with the cat when I left. That night I met some of our staff (Wonde, Hannah, Gulma) at a restaurant for a goodbye meal. It was really great to hang out with them.

Friday was one of the meeting days in the morning, and I had a last supper at the home of our cook Yeshi who also invited Sisay and his family. I was relieved Sisay was there since Yeshi was set on stuffing us with enjera and doro wot, and I knew I could not eat a lot of it myself. Sisay's family helped eat all the extra helpings we were served. It was a good end to the week.Wonde took Bereket and me to the airport at 5 am the next morning. I kept the cat in my container all night so I could find her in the morning. I put her in the cage, got my bags, and Bereket, Wonde, me, and Bereket's parents drove to the airport. We said tearful goodbyes at the departure terminal, and Bereket and I went in.

|

| Departure from Addis with Barry's parents |

At the airport in Nairobi, I was treated like a VIP. The vet service met me as I exited the plane, bringing with them Charley's entry permit. They then escorted me to the front of the UN immigration line and down to baggage claim. Rebecca eventually met me there and we left with my bags and Charly, back to our apartment in Nairobi.

By that time I knew Bereket was about halfway through his journey, and I was watching my flight tracker until I saw his plane landing at about 2am our time. Whatsapp lit up as Jean (Rebecca's mom) and Oren were meeting Barry at Dulles. They had photos of him coming out the doors at Dulles. (No problem at immigration). They drove him down to Harrisonburg Virginia that night where he rejoined his host family-- former Reps. Bruce and Rose and their son Jacob, Bereket's other friend.

It was a true answer to prayer to see the photo I received the next morning, of all of them together.

|

| Oren, Jacob, Rose, Bruce, Bereket in Harrisonburg VA |

Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.

Hebrews 11:1

This is the end of our Ethiopia journey.

Wednesday, August 7, 2024

Memory Stuffed Interval Between Two Assigments

I shouldn't make it sound like we are getting off easy

though. On the same morning, the Kenya/TZ Rep emails started arriving and I am

fully authorized (and required) to receive and answer the Kenya/TZ Rep

emails.

We scheduled all of our doctor visits and other required

appointments (getting a criminal background check for our new position as well

as many documents notarized.) Fortunately, Dave and Jean can make one of their

vehicles available to us, and we ran around town over the week doing various

shopping and business trips. We were also able to see my parents several times

during the week at their nearby retirement community.

|

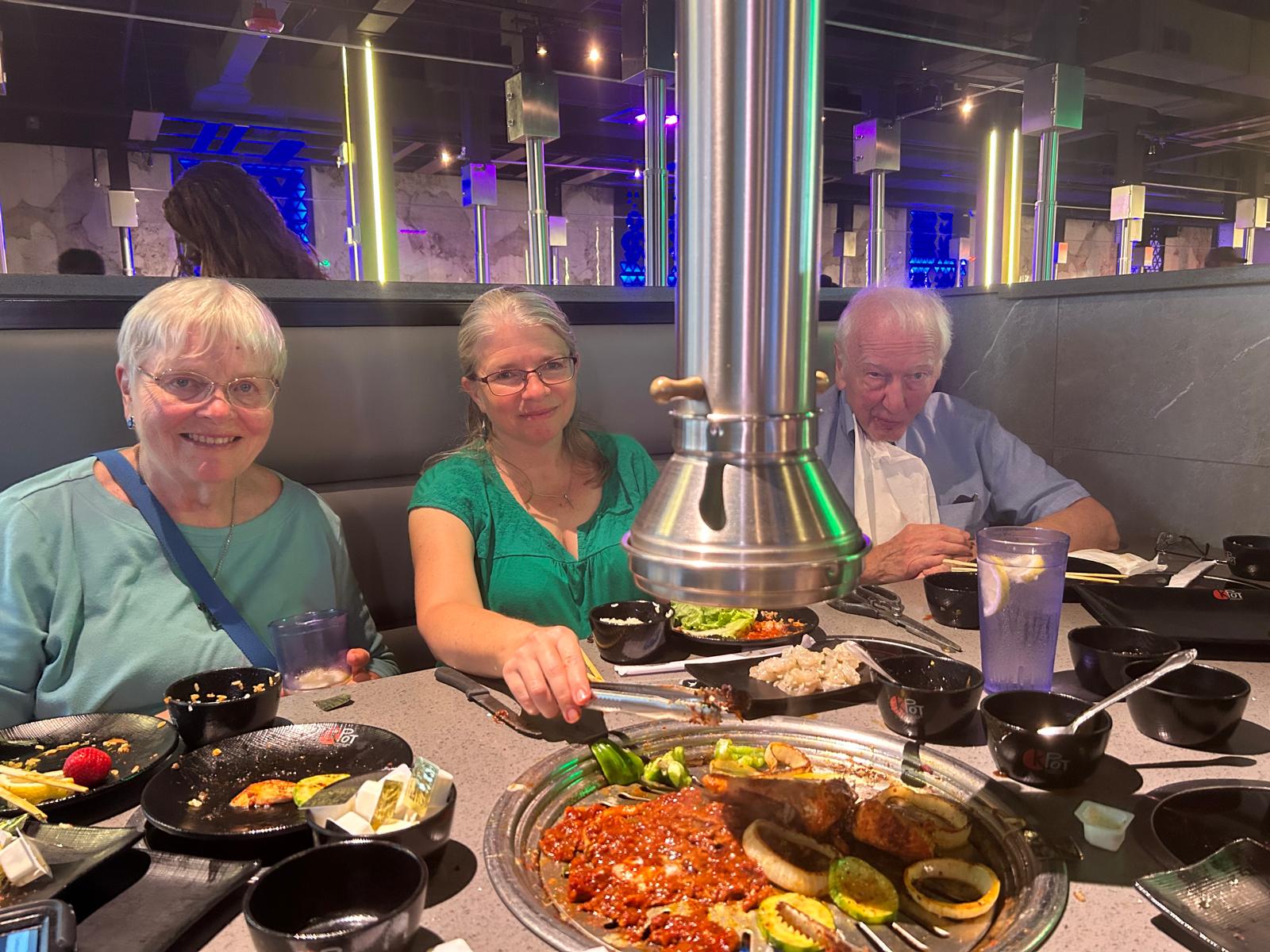

We went on Sunday to North Baltimore Mennonite Church, our home church, and heard our former boss, Ruth Clemens, share about the vanishing art of Christian hospitality and its importance in building the body of Christ. (Are we growing more and more isolated from each other in this digital age? Can we continue to affirm our community values through simple hospitality? meeting together-- sharing food, potlucks?) Afterwards Oren had us go out to a Korean BBQ he had tried with grandparents. It was an interesting kind of K-pop fusion restaurant, the likes of which I have never seen.I should add a note that Rebecca started to feel sick by our second day in Baltimore and tested positive for COVID. Almost miraculously, none of the rest of us got it, and that included 4 elderly grandparents! Fortunately, her symptoms remained mild.

The second week promised to be a highlight. Ever since 2020,

we have made a connection with some acquaintances who have made a lovely Swiss

chalet-style Bay house available to us for a week. We love the retro 1970s

Brady Bunch decor, and the huge windows overlooking the Chesapeake Bay. It is

so comfortable to be in, and they have this incredible oversized croquet set

that is awesome to play. The Bay is just a hundred feet away, and we bring our

stand-up paddleboard, kayak, canoe, and fishing gear down to use during the

week. We also invite friends to visit us.

Jonathan and Fletcher left on Saturday morning with David and

Oren for our next destination. We had planned a Mosley family reunion earlier

this year at a place called Lake Anna in Virginia. We rented a vacation rental that

started that Saturday. Jonathan and the kids went on while Rebecca and I

cleaned the previous place.

|

David and I went fishing a number of times along with cousin

Fletcher. We caught several really big catfish in the marshes near our rental.

It was fun to catch them, although we did not keep them, as I am not a big fan

of catfish meat. Rebecca really enjoyed going out on one of the kayaks at the

rental and birdwatching in the quiet evening.

We also had a quick visit from some old friends from our New York days. Courtenay came with her two kids Asa and Alexander. Asa and Oren were born very close together in Poughkeepsie. They had not seen each other for at least a decade. It was a nice surprise to have this serendipitous visit as they were passing through Maryland on the way from New York to Virginia.

When Paul Sack’s family got back we had a final meal and

talk with them then moved back to Rebeca’s parents’ for our last night. My

parents came over and we had a big salmon dinner and a time of prayer. It was

hard to believe that it was already over. (or that it had even happened!)

We did our best to leave everything in good condition. We

had done yard work at their house, and hopefully left things looking good.

This blog is being completed on Brussels Air over the

Atlantic. A fairly uncomfortable plane on this leg.

We will start a new blog for the next phase of our lives.

Bonus Photos: